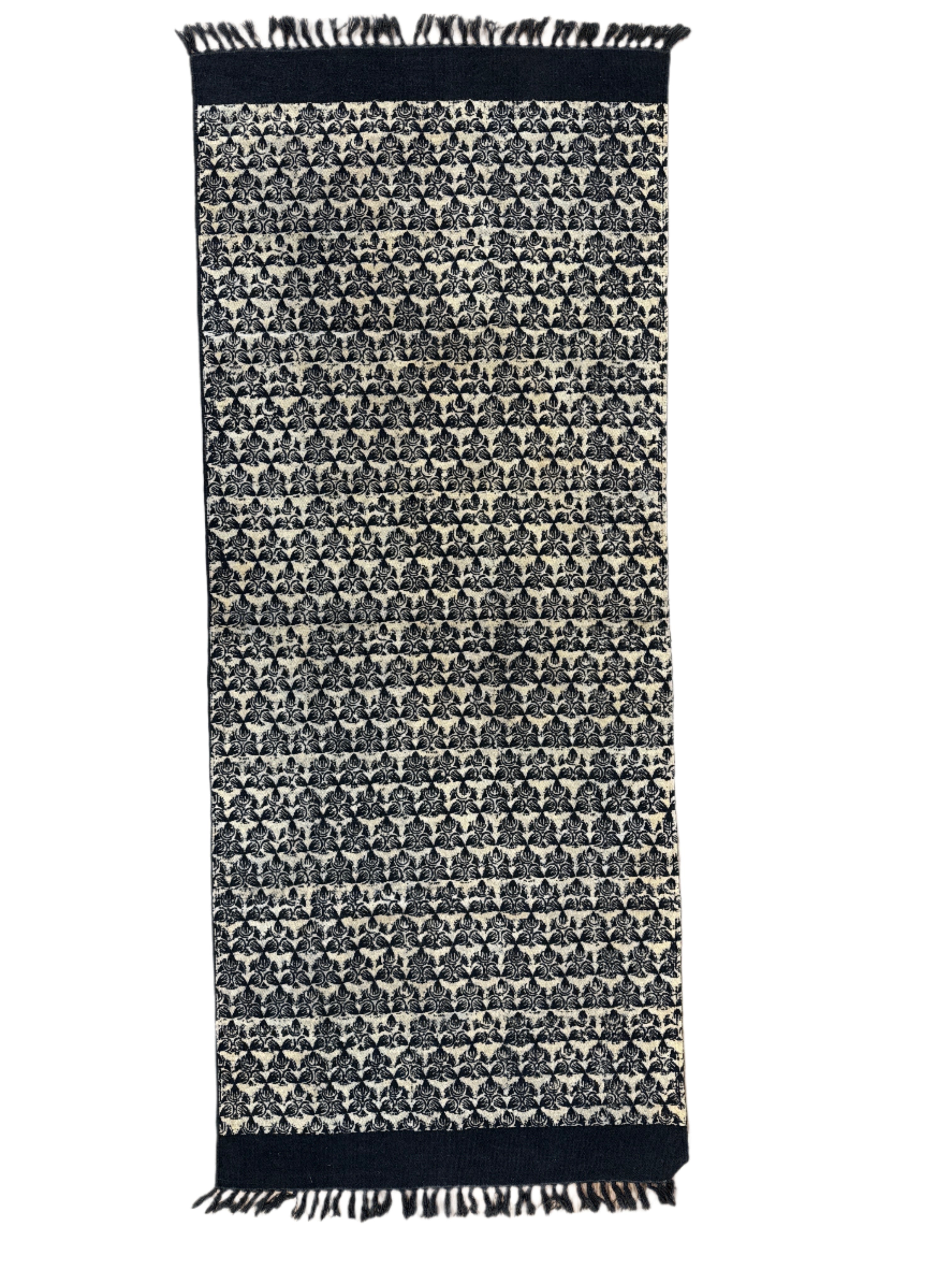

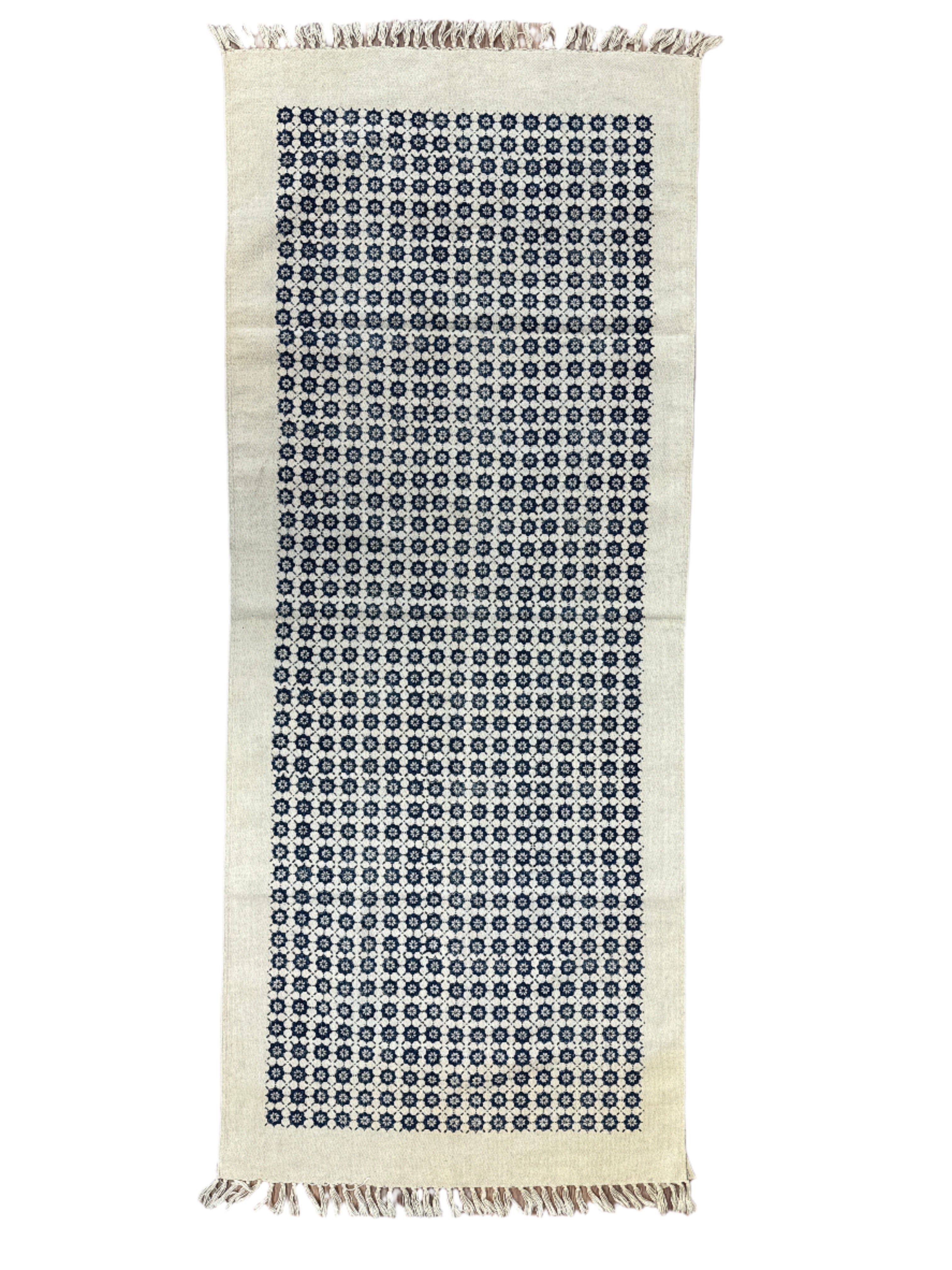

Sufiyan Ismail Khatri, a member of the Khatri Community in Kutch, Gujarat, is preserving the 4,000-year-old tradition of Ajrakh hand-block printing, originating in the Indus Valley civilizations. His collection, featuring rugs, wall hangings, pillows, and household items, showcases intricate, perfectly symmetrical Ajrakh designs that celebrate unity and order.

Sufiyan's commitment to reviving the appreciation for this ancient craft extends beyond his designs. He recognizes the laborious process involved in creating Ajrakh textiles. Each piece undergoes a multi-step process of washing, printing, dyeing, and boiling. The intricate patterns are carved into teak wood blocks, using complex mathematical calculations and artistic abstraction to achieve infinite design variations.

The dyeing process involves a unique technique of resisting the fabric with a paste of lime, gum-arabica, and clay, allowing only certain areas to absorb dye. This method is exclusive to Ajrakh and results in the distinctive two-sided designs. Artisans use natural dyes like indigo, madder, pomegranate skin, turmeric, henna, lac, logwood, sappan wood, and iron to create various colors. After printing, the fabric is washed, dried, and finished with tassels or fringes by women artisans from neighboring villages.

Ajrakh designs are more than just ornamental; they hold cultural significance and reflect the region's landscape. Motifs like the 8-pointed star, champa kali, badam-bhutta, night skies, ray-shaped florals, rosettes, riyal, taaviz, kan-karak, mifudi, koyaro, jaalis, mihrabs, and garden designs are symbolic of the nomadic Maldhari Muslims who traditionally wore Ajrakh-printed textiles.

Khatri emphasizes the importance of reviving the community's pride in Ajrakh. Before the 1950s, craftsmen were supported by the local community and took great pride in their work. The introduction of the global market and industrialization has led to a decline in this reverence. Khatri aims to bring back the authenticity and value of Ajrakh in modern contexts.

Visiting Bhuj, India

The first time we visited Sufiyan Khatri’s natural dye block-printing studio located outside of Bhuj, in the Kutch, we were so excited to see all the colors, all the patterns- we immediately began to imagine all the possibilities. We were so excited we were positively vibrating. Picking up on our frenetic energy, Sufiyan said: “First we take tea, then we talk business.” Lesson learned. Thereafter, upon entering an artist’s studio anywhere, we respectfully await cultural cues.

Since then, we’ve visited Sufiyan several times and he always has the tea ready- along with stacks and stacks of natural dyed block printed fabrics. He knows we’ll spend the day with him- and we’ll review every single latest block design and every single new product, too. He invites us for lunch, prepared by his wife, Hamida. Like many women in this region, Hamida ties bandhani and while our lunch is digesting, and we’re sipping more tea, she pulls out examples of her handwork as we offer our gifts of chocolate. And then we return to the studio and we get down to business. At one point his daughter pops in for a visit. Showing her his long tally of columns of figures, Sufiyan says, “She is so quick and smart! Just like her momma!”

As the afternoon wears on, we begin to narrow our options for block printed natural dyed canvas rugs, cotton quilts and an array of sumptuous cotton and silk scarves. Gathering his thoughts, Sufiyan begins to write the order as Jody digs in her purse for “The Notebook” so she can make a record, too.

Growing up, Sufiyan credits his grandfather, a renown block printer and community leader with installing basic skills in childhood. Lessons included learning to fix his own bicycle or learning to repair plumbing and water issues necessary to any dye studio, to being called upon to serve hospitality to the many guests who visited the family’s atelier. His grandfather insisted Sufiyan understand every aspect of the block printing business- including learning to carve the wooden blocks. Later, working alongside his father, Dr Ismail Mohammed Khatri, who is widely credited with reviving the complex ajrakh double-sided natural dye printing process in the Kutch, Sufiyan perfected his skills.

Today, Sufiyan welcomes international visitors to his studio and he travels to teach and share his knowledge with practitioners all over the globe. Like artists everywhere he soaks up inspiration from many sources.